Objective: Aesthetic enrichment to be experienced

Outcome: Aesthetic enrichment is experienced

Measure: Aesthetic enrichment experienced

Short description

By aesthetic enrichment, we mean an experience that comes through the senses that is special and outside the everyday. This might include being moved or challenged through feelings such as beauty, awe, discomfort, joy or wonder.

Full description and underpinning theory

Full description

This outcome is about how aesthetic enrichment, from pleasure to challenge, can result from cultural engagement. Aesthetic enrichment is experienced through the senses, elicited by aesthetic qualities perceived in the artwork or experience, through properties such as harmony and form. It involves experiences outside the mundane, of beauty, awe, joy and wonder; potentially offering a sense of escape or captivation, or feelings of being moved, challenged or transcending the everyday, extending to deepest experiences of a sense of flow, or the numinous or spiritual realms.

This outcome can include enjoyment from participation in arts experiences that are familiar, known as aesthetic validation, or unfamiliar, known as aesthetic growth or challenge. This outcome is not necessarily a shared sense: it can be experienced and enjoyed alone, unlike Outcome 5, which is about how cultural experiences connect people to each other. A desired endpoint is more and deeper experiences of aesthetic enrichment, as these are unlimited and can be continually generated. Further engagement with similar or other enriching cultural activities may be inspired. This outcome corresponds to UCLG’s cultural element of ‘beauty’ (UCLG, 2006), but is broader, in recognising that cultural enrichment can also come from experiences that are not beautiful, but challenging or awe-inspiring.

Theory underpinning this outcome

This outcome corresponds to UCLG’s cultural element of ‘beauty’ (UCLG, 2006); beauty created through human activity and enjoyed by audiences or participants (UCLG, 2006); aesthetic characteristics including harmony and form (Throsby 2001). Definition of beauty: it has to be interesting, have a memorable form and promote a desire to revisit (Gardner, 2011).

Aesthetic enrichment: the extent to which the audience member was exposed to a new style or type of art or a new artist (aesthetic growth), and also the extent to which the experience served to validate and celebrate art that is familiar (aesthetic validation) (WolfBrown, n.d.).

Aesthetic enrichment may come from enjoyment of exposure to style of art or artist that is familiar (aesthetic validation) and/or enjoyment of exposure to a style of art or artist that is new (aesthetic growth or challenge).

Evidence that this outcome occurs

Visitors experience high levels of aesthetic enjoyment in modern art museums (Mastandrea, Bartoli & Bove, 2009); Stendhal syndrome, a psychosomatic disorder that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, fainting, confusion and even hallucinations has been documenting as occurring when an individual is exposed to an experience of great personal significance, particularly viewing art (Nicholson et al, 2009). Attendance at music concerts engenders feelings of enthusiasm, joy, happiness and excitement (Evans et al, 2016).

The value of literature is its capacity to compensate for loss: “Through art we can feel, as well as know, what we have lost; in art, as in dreams, we can occasionally retrieve and re-experience it.” Literature also has a capacity for immediacy, an ability “to transmit sensations and sentiments”. Its “directness to life” draws from a commitment to the rightful labour of writing, and to its veracity, “a responsibility to the accurate word” (author Shirley Hazzard).

Some people talk about the spiritual value of art, but it is generally not something that most people can articulate. More likely, people talk about “being transformed” or “renewed” or “energized” by an arts experience (Brown, 2004).

Activities contributing to this outcome

Activities

As of April 2021, there were 90 activities in Takso selecting this outcome with 19 completed and evaluated. Types of activities undertaken to achieve this outcome include:

- Collection access

- Commissioning of public art (acquired)

- Commissioning of public art (not acquired)

- Exhibitions: of arts and objects in all forms

- Gathering, celebration or ceremony

- Performances: performing arts all forms

- Publications in all media

- Research and development

Results

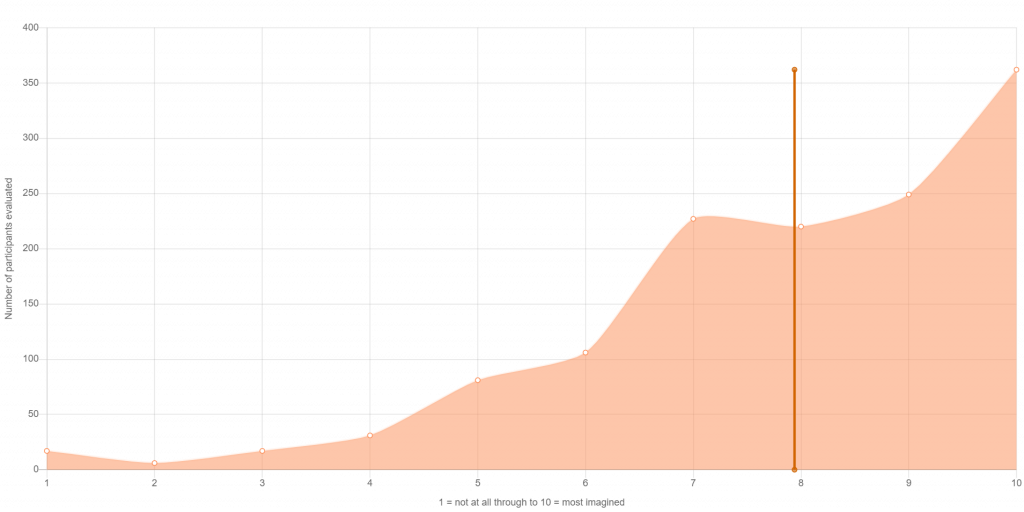

Over the 19 completed activities that addressed this outcome, 2500 people responded to the evaluation question. On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being not at all and 10 the most imaginable, respondents reported an average attainment of 7.95 for this outcome.

Aesthetic enrichment experienced

20 activities / 2500 responses / Average attainment 7.95

Processes

The same cerebral areas involved in emotional reactions are activated during the exposure to artworks (Claudia, et al. 2014). While researchers Evans et al (2016) determined that ‘immersion’ was an outcome of audience members’ attendance at classical music concerts, it could be seen as a process towards the actual outcome of ‘enrichment’. By enabling audiences to become deeply immersed, the music then was more likely to enrich them. Other causal factors identified in this study include the ‘uniquely intimate, relaxing and comfortable environment’ of the venue.

Evaluation measure

Experience of aesthetic enrichment

References

Brown, A. (2004). The Value Study: Rediscovering the Meaning and Value of Arts Participations. Hartford CT: Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism.

Claudia, I., Giulia, F., Raffaello, S., Carlo, F. (2014). The Stendhal Syndrome between Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience. Rivista di Psichiatria. 49(2):61–6

Evans, J. McFerran, K., White, T. & Yue, A. (2016). Investigating Wellbeing Outcomes: The Melbourne Recital Centre, Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

Gardner, H. (2011). Truth, beauty, and goodness reframed; educating for the virtues in the twenty-first century. New York: Basic Books.

Mastandrea, A., Bartoli, G. & Bove, G. (2009). Preferences for ancient and modern arts museums, Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts, 3(3), 164-173.

Nicholson, T. R. J., Pariante, C., McLoughlin, D. (2009). “Stendhal syndrome: A case of cultural overload”. Case Reports 2009: bcr0620080317. doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0317.

Throsby, D. (2001). Economics and culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) (2006). Agenda 21 for Culture. Barcelona: UCLG. Retrieved from http://www.agenda21culture.net/index.php/docman/agenda21/212-ag21en/file

Wolf, D. & Holochowst, S. (n.d). Investing in the long view. Sounding Board 31 Retrieved from http://wolfbrown.com/images/soundingboard/documents/WB_SoundingBoardv31_online.pdf